Background

As the Korean War was coming to a close in 1953, the Department of Defense was still disgruntled with not having a MiG-15 in their possession to asses its capabilities. With the new age of jet-powered aircraft trying to assert air superiority, the U.S.’ F-86 Sabres were pitted against Russian made MiGs which were giving pilots a run for their money.

Determined to get their hands on one, the DoD devised a plan and although it’s surrounded by many different controversies, including its origins and effectiveness, they eventually got what they wanted.

Operation Moolah

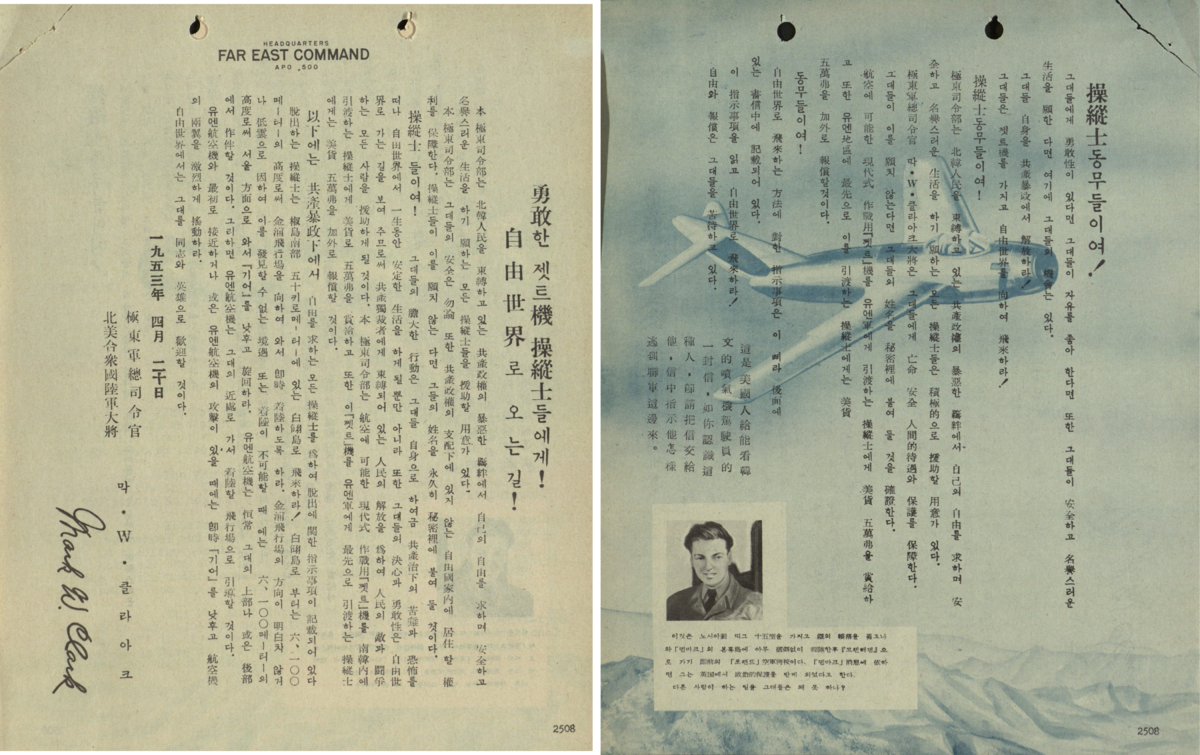

The plan was simple. Offer money and asylum to whichever pilot, Russian or Korean, defected and brought a MiG-15 to an American base. On April 26th, 1953, just months before the official end of the Korean War, two B-29 Superfortresses dropped over a million leaflets over what is now North Korea urging pilots to defect. The text offered protection, refuge and a $100,000 reward which is equivalent to nearly $1 million today.

The operation was seemingly a dud if not outright having an adverse response. Over the next months, U.S. pilots reported seeing decreased MiG-15 activity, some even stating they haven’t seen them for days at a time, an occurrence that was not common.

The reason for this was the regime’s reassessment of their pilots. Many were grounded to be interviewed again and have their loyalties tested.

Lt. No Kum-Sok

On September 21st, 1953, soldiers at the Sunan Air Base in Pyongyang, North Korea, were surprised to see a MiG-15 entering their airspace and land on their airstrip.

Lt. No Kum-Sok, a 21-year-old North Korea pilot, emerged from the jet, tore up a picture of the then current leader Kim Il-sung and surrendered. He was quickly taken into custody and interrogated by the Fifth Air Intelligence Office and later debriefed.

He declined the cash reward and opted for a U.S. citizenship and free education. Settling in Florida, he became an aeronautical engineer for Grumman, Boeing, Lockheed as well as other well-known aviation companies.

Controversy

Although not regarded as such by many, some people view the operation and No as a traitor to his own country that shouldn’t have been given asylum. In the military community the act is viewed as incredibly dishonorable and one that shouldn’t be glorified.

In addition, No said he had no idea of the cash reward or any other perks his actions would guarantee him, which is quite odd. Also, it was the CIA that dissuaded No from taking the cash reward and instead move to the United States.

Aftermath

The MiG was disassembled and sent over to the United States to be examined piece by piece. Put back together again, it was rigorously flight tested by some of the best pilots, Chuck Yeager included.

In the end, the MiG didn’t seem to be all that superior to the F-86 Sabre it was comparable to. It is now at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio.